The gravest threat facing community conservation in Kenya is not overgrazing

The greatest conservation dilemma for community land in northern Kenya is the same dilemma facing its economic wellbeing. It is the same structural dilemma that makes an inequitable society where some families do well and others do not. The issue may lead to overgrazing but it is just as likely to lead to political turmoil, instability and opportunism.

Conservationists like myself can be tone deaf or worse, patronizing when it comes to communities and conservation around the world. I detest the lecturing tone of many NGOs and it seems hypocrisy is an endemic disorder for many of them. How then to try to identify such a political issue without the loftiness or condescension? Fortunately, the issue is not at all unique and it has been identified by many Kenyans before me. It exists worldwide and despite textbook focus is rarely not a problem for all governments , small and large. Trump’s abuse of America’s public lands for the benefit of only a few fossil fuel companies is a glaring example.

‘A tragedy of the commons’ . It is a concept coined long ago in the UK to describe grazing problems on communal land. The idea is simple; overgraze while you can because if you don’t, someone else will.

The commons dilemma for community ranches in Kenya though is not limited to livestock grazing alone as many might suspect. If herds are managed collectively on a rotational basis, it results in an increase in the capacity of the land to sustain even greater stock numbers (and so livelihoods). This has been quite achievable for some communities with the will to change practices. The trickier and more pressing dilemma is membership and voting rights.

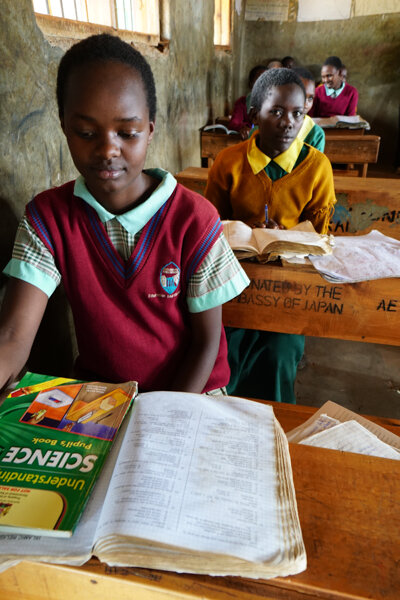

Most group ranches in Kenya are collectively owned by the members. Many of the ranches were incorporated in the early 1970s and the founding members were in the low hundreds. Today those same ranches have many thousands of members many of whom have moved elsewhere for lack of space or opportunity. Some basic math will show anyone with an interest, that the system is all ready unsustainable. How can these ranches expect to take care of the future generations when every child of every future generation will be a group ranch member? They can’t. Inheritance is a tricky business even for wealthy land owners who must make cold and calculated decisions to keep properties viable and within their family. It is foolish to assume that these same basic economic pressures do not exist for the community ranches.

What is worse is how the commons problem effects the membership and it’s politics. The system is geared to favor the strong man and not to safeguard the larger populous. If a neighbor chooses to only have two children because they are all she can afford to educate, she may find that her neighbor chooses instead to have 12 children without enough money to educate any of them. Despite those decisions, it is then the larger family who will become a more powerful political unit, voting for their own members for seats of leadership. It is for this reason, in all group ranches, that the large families have the lion’s share of power and influence. Furthermore there is rarely any reward or benefit for the parents who have made good decisions for the welfare of their family An alternative system where membership and voting rights are reduced to a sustainable but fixed amount, is the only way that these communities can remain viable and just. Unfortunately, it is these same strong men and their constituents that communicate for the ranches (since they are always in the seat of power) and will likely oppose any change to the status quo. When challenged community leadership tends to portray their structure as rooted in their own traditions. And yet, there is nothing traditional about a ranch Chairman (nor for that matter the fixed property that necessities it) and it is especially untraditional to have the decision making in the hands of only one individual. The conditions are perfect for cattle barons to flourish as well as politically connected individuals eager to launder money and evade taxes in such an unregulated environment. Better governance would likely reflect a more traditional and just style of leadership.

Kenya is frequently applauded for its conservation achievements. Within its borders are countless endangered species and ecosystems as well as thriving herds of animals scarce in much of Africa. The country should be proud of the hard work its citizens, communities, and government have made on behalf of their wildlife, their land and their water. This work has had a huge impact on the economy of the country, helping to bolster a thriving tourism industry and becoming a showcase example of wildlife paying for itself.

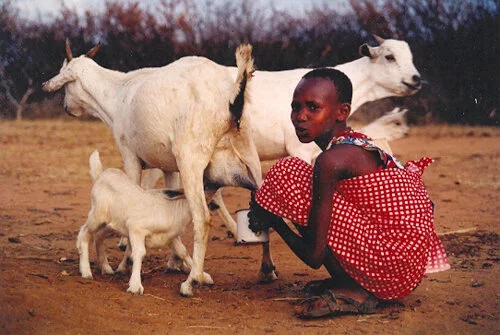

Like anywhere though, there always exists an opportunity to improve and while many of the obstacles to conservation in Kenya appear unsurmountable many of those same problems are actually the country’s greatest opportunities. Opportunity for land as well as it’s people. The communities in northern Kenya are wonderful places to visit; beautiful areas and home to vast acres of wildlife habitat. Pastoralism is more gentle to the land than other kinds of farming and we should be thankful to these communities since they are part of the reason that large game still exists in Kenya.

A few Kenyan conservation organizations have tried to address the commons issues but it is a hard problem to tackle and it is one that will never trigger huge donations like images of poached animals or mad technological conservation solutions like drones and thermal imaging. It is nonetheless, in my opinion, the most important problem (as well as opportunity) facing conservation in Kenya. If conservation can be achieved in Kenya while also achieving a more just world then we would be fools not to strive for it. I hope that more pressure can be applied to this non-glamorous issue so that people, land, water and biodiversity can simultaneously benefit from some small changes in governance and economics.

James Christian